August 2003 - Les Inrockuptibles

(France) (Translation below)

(Cover)

(Cover)

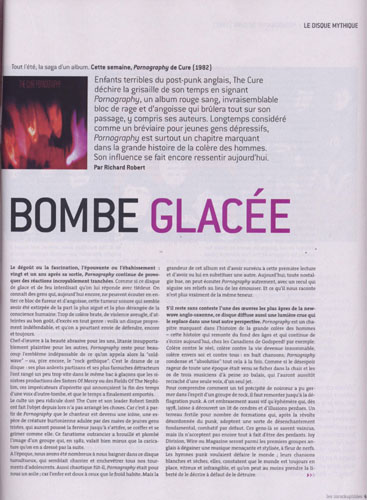

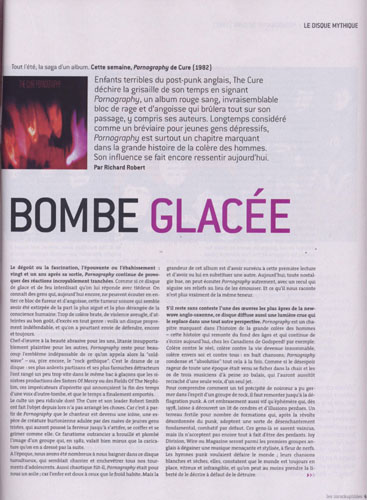

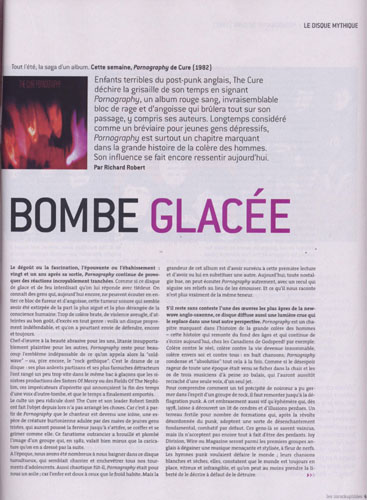

Icy Bomb

-

by Richard Robert

"Enfants

terribles" of the British post-punk, The Cure tear apart the dullness of their

time by adding to their name Pornography, a blood-red record, an

incredible block of rage and anguish that will burn down anything in its path,

including its authors. Long considered a breviary for depressive young people,

Pornography is above all a key chapter in the history of human anger. Its

influence still makes itself felt today.

Disgust

or fascination, horror or astonishment: twenty-one years after its release,

Pornography continues to elicit incredibly extreme reactions. As if this

record of ice and fire would forbid that one would react mildly. We know

people who, even today, can't listen in its entirety to this block of fury and

anguish, this sonic tumor that seems to have been extirpated from the most

cutting and the most deranged part of the human conscience. Too much raw

anger, blind violence, attacks on good taste, excess of all kinds: here is a

record, veritably undefendable, that yet we feel compelled to defend, again

and always.

Masterpiece of abrasive beauty for some, unbearable plaitif litany for others,

Pornography remains for many the unsurpassable emblem of what will since be

called "cold-wave" - or, worse yet, "gothic rock". It is the drama of this

record: its most ardent partisans and its most savage detractors have placed

it a bit too quickly in the same basket with the sinister productions of

Sisters Of Mercy or The Fields Of The Nephilium, these operetta imprecators

who were announcing the end of time with voices from beyond the tomb, and whom

time has finally taken away.

The

slightly ridiculous cult that The Cure and its leader Robert Smith have been

the object of since then hasn't helped. It was starting with Pornography that

the singer has become an icon, a kind of Burtonian creature adulated by

countless sad young people, who would push the fervor up to dressing, wearing

their hair and make-up just like him. This extreme fanaticism has clouded and

weighted down the image of a group that, in 1982, was so much more than the

caricature that some will draw up of it.

At the

time, many among us had dived into this tumultuous record that seemed to carry

and entangle all our adolescent torments. As chaotic as it was, Pornography

was for us a refuge; for an inferno is welcome to those haunted by cold. But

the glory of this album is to have survived the first "reading" and to have

been able to substitute it with another. Today, all nostalgia aside, one can

listen to Pornography in a different way, with a distance that sharpens its

landscape instead of flattening it. And what it tells us today is of a

different substance.

While it

remains uncontestable one of the harshest works of the Anglo-Saxon new wave,

this record also gives off a raw light that places it in a different

perspective altogether. Pornography is a key chapter in the history of the

great human anger - this history that goes back to the depth of time and that

continues to be written today, for example by the Canadians of Godspeed!.

Anger towards reality, towards a life become unspeakable, anger towards

oneself and everyone else: in eight songs, Pornography condenses and

"absolutizes" all that at once. As if the raging despair of an era had come

lodge itself into the flesh and bones of three musicians barely twenty years

old, who would spit it out at once, with one voice.

To

understand how such a concentrated darkness could take birth in the spirit of

a rock band, we need to look as far back as the punk deflagration. This

flare-up, as vivid as it was ephemeral, that since 1978 has left an open bed

of ashes and lost illusions. A fertile ground for numerous formations that,

after the disordered punk revolt, adopted a kind of fundamental

disenchantment, combative by default. These people know they are defeated in

advance, but haven't quite accepted yet to be losers. Joy Division, Wire or

Magazine will be among the first British groups to create a new kind of music,

menacing and stylized, touching raw nerves. Punk anthems wanted to dismantle

the world; but for their part, their songs, desolate and dry, notice that the

world is still in place, glassy cold and impassable, and that one can at least

take the liberty to decry it if it cannot be destroyed.

With

this post-punk wave, rock music returns to introspection. The return itself is

full of bitterness: the personal sphere is just as oppressive as the social

one, staying just as unchanged. If it didn't succeed in transforming the

world, neither did punk free individuals of their own chains, their own

internal conflicts. From this terrible observation, Ian Curtis, the leader of

Joy Division, will draw the most radical conclusion. His suicide, on May 18,

1980, may well have been a strictly private affair, but it rang the final bell

for a collective utopia that The Cure will soon pronounce the funeral oration

for.

On its

first album, Three Imaginary Boys (1979), The Cure plays sharp and almost pop.

It is in appearance only a modest group from a far suburb south of London,

something like a touchy little cousin of the Buzzcocks. Ill at ease in their

own skin, the three teenagers of The Cure compensate for their

almost pathological shyness through a musical work with a singular charm, made

of an expressive minimalism, nervous tension and melodical freshness. His face

drawn, Robert Smith, who is already singing with that voice of a child, a

little distant and sullen, resembles the description that Andre Breton gave

the count of Lautreamont: he has "the star on his forehead and the gaze full

of a fierce melancholy".

Very

quickly, The Cure becomes the catalyst for his only obsessions. Over two

albums, Smith will considerably decide the aesthetic path of his band. Less

and less well-formed, the songs of The Cure seem to inhabit a sonic palette

comprising all the shades of grey and white. They take the uncertain shapes of

a man at bay, as if poised at the edge of a reality he would like to run away

from and an interior universe where he fears getting lost. Seventeen Seconds

(1980) covers itself with a misty veil that aligns The Cure on the side of

atmospheric songwriting, somewhere between Nick Drake's Five Leaves Left and

Brian Eno's Before and After Science. With Faith (1981), the veil becomes

opaque: the mist turns into twilight, the songs dampen themselves in layers of

sepulchral synths. Affected by family deaths (the drummer's mother and Smith's

grandmother having died that year), the group plunges its music into a

sulpician atmosphere that only very rare lightning strikes tear apart.

It is

from this bottomless pit that will emerge the naked and burning truths of

Pornography. "After the very trying tour that followed Faith, I was feeling at

my lowest," recalls Smith. "I was angry, without hope. The band itself was

disappointing me. I was convinced that we had never gone as far as I wanted:

every time we had backed off at the last moment, as if frightened. I wanted a

sound of extreme violence, that could express all my frustrations. the songs

on Faith were too gentle to transmit anything but a feeling close to giving

up. Only one song made an exception: Doubt, a more aggressive and not very

accomplished bit that we had recorded at the very end of the session, to keep

the record from being too formless. It was this path that I wanted to follow

until the end with Pornography. If we were to quit, might as well do it with a

gigantic 'bang'!"

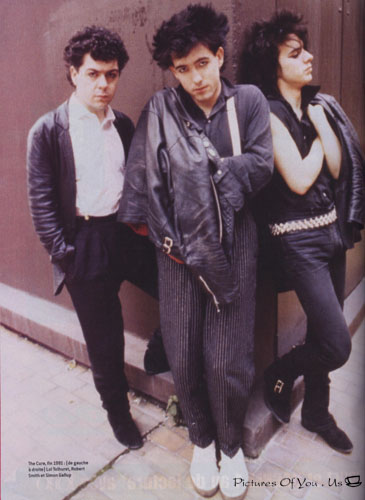

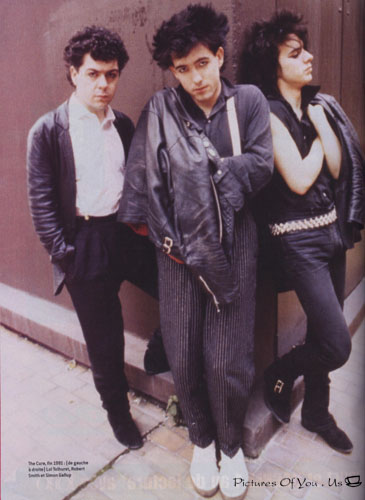

A short

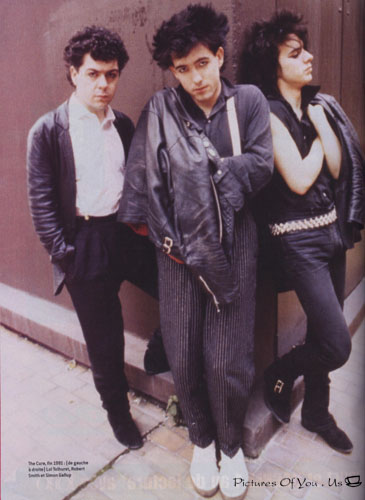

time after Seventeen Seconds, the line-up of The Cure had stabilized around

Robert Smith (voice, guitar), Simon Gallup (bass) and Lol Tolhurst (drums). A

triangle that, in the eyes of many fans, represented a kind of perfect

equilibrium. Its force resided in the total trust, almost blind, that binds

its members. Tolhurst is a childhood friend of Smith's, already present at his

side in the bands that preceded The Cure. Gallup, for his part, is the twin

brother and confidant that Smith has always dreamed of having. "The Cure was

our only true family," says Tolhurst today. "That made the rifts that followed

only more painful."

This

beautiful internal alchemy will fall apart through the actions of Smith

himself, principal agent of a disorder that will only stop with the

dissolution of the trio in June 1982. "From the moment when I decided I was

going to write this album by myself, the friendship that reigned within the

group was broken. Simon took it as an act of treason. Consciously or not, I

was looking for this chaos. I wanted us to go deep within ourselves, to

confront what we really were. The state of physical deterioration I put myself

in had only this objective."

For

this, Smith didn't go empty handed. In the months preceding Pornography, he

engaged in a long voyage of drugs and alcohol that will inspire his most

hallucinatory lyrics. When he is not roaming the streets of London under the

influence of LSD, the singer spends most of his time with Siouxsie & The

Banshees bassist Steve Severin, with whom he makes plans for a second career -

under the name of The Glove, the two will release in 1983 an album under

influence, Blue Sunshine. This sulfurous friendship will only attract Gallup's

resentment and throw more oil on the fire of Pornography.

Even

before entering the studio, the tone is then given: the fourth album of The

Cure will be the broken mirror of a psyche in an advanced state of

destructuration, but also the last act of bravery from a trio that knows

itself condemned to implode. The chance of the group, if one dared to call it

that, is that, like a last sign of connivance, Gallup and Tolhurst find

themselves almost in the same deep dark place as Smith. "We were on the border

of psychosis," admits the last. "We spent days on end without sleep and took

all the drugs we could get our hands on. We were in a much more terrible state

than we imagined... Fortunately, we were young. That's what allowed us to get

away with it."

In

January 1982, the three musicians move into RAK studios, in the center of

London. During long weeks, they will barely ever walk out and will not receive

any visits. They record during the night, sleep during the day on the spot.

The bottles they drink continuously amass into a corner of the studio, ending

up into forming a wall behind which, says Tolhurst, you could hide. Smith:

"Outside, it was raining all the time, it was always dark. I was feeling

terribly weak, ill at ease in my body, I wanted to tear my flesh off. But it

wasn't all so terrible or unpleasant, because we had a feeling that we were

doing something unique, incomparable. And that is a wonderful feeling."

Incapable of communicating with his partners, Smith is convinced that he is

the only one who can control the game. But Gallup and Tolhurst will be a lot

more than two executants overwhelmed by events. Far from weighing down the

songs, the aggressiveness and distress that dominate them will on the contrary

give them an additional charge. Tolhurst: "All three of us in a room, on the

way to creating this improbable record, we were a bit like Cocteau's 'les

enfants terribles'."

Mike

Hedges, the producer of the previous records, was replaced by Phil Thornalley:

his perfectionist approach didn't go well with Smith's aspirations, who wanted

to hear "a wall of sound, an indistinct noise." The demos recorded by the

singer provide the substance for a music stripped naked, breaking with a great

and strident effort through the cocoon it had taken refuge in until then. On

Faith, life according to Smith resembled a non-revealed mystery; now, it only

appeared to him as an obscene act, an insane exhibition that he tries to

describe with a turbulent torrent of words. Looked at it as such, the long

opening piece, One Hundred Years, is like a bloody matrix from which the other

seven songs of the record burst out. "I was so disgusted with myself and the

whole human race that everything looked pornographic to me. The title and the

content of the record were born from this unbearable observation."

Smith

says he wrote most of the songs on Pornography on drums, "to get the tension

out, beating on something rather than on someone." Martial (The Figurehead),

tribal (The Hanging Garden, Pornography) or simply hammered out (Siamese

Twins, A Strange Day, Cold), the rhythms give the heavy pulsation to a record

where every song breaks free of the verse-chorus format. Pornography - which,

according to Smith, "doesn't express violence, but the incapacity of being

violent" - sounds as if it had been recorded in a prison, undoubtedly because

it tells the story of a man, a group and an era closed in on themselves. The

sound, oppressive in the extreme, is full of echoes that catch the group in a

vertiginous, inescapable spiral. Every note, every vocal burst is as if

reabsorbed into the tension that generated it.

When the

album is released at the beginning of May 1982, the reaction of the critics is

on the measure of the blows carried by the group: murderous. In England, some

reviews are so violent that they seem written in a state of self-defense.

Shocked, a journalist writes: "If Faith took no prisoners, Pornography doesn't

even recognize its allies." The NME expresses its revulsion through a simple

statement: Pornography is "Phil Spector in hell." The electrified wall that

the group has erected around itself is so compact and so unfriendly that it

discourages any musical analysis.

The tour

that The Cure embarks on almost one month before the release of the album is a

disaster. Exhausted both physically and mentally, the trio emits such a

negative energy that it affects its whole entourage and generates a countless

fights. In a very beautiful work that retraces the history of The Cure through

its concerts (* The Cure: Clinical Prescriptions - Experiences 76-87), a few

photos stand witness to the chaos that reigned on stage. Faces slashed

with traces of lipstick, the members of the group look like automated soldiers

who can only go on fighting mechanically. The public tries, for better or

worse, to hang on. Tolhurst: "We were playing the full length of a record that

nobody had heard. It was rather... intense. I remember a concert we did on a

Sunday afternoon in Germany. It was a huge hall, and there were only about one

hundred people there. We had asked them to come closer to the stage. After

that, we proceeded to play this extremely harsh and somber music, while the

light were streaming in through the windows. It was surreal."

After a

show in Strasbourg, a violent fight erupts in a bar between Smith and Gallup.

It signs the death certificate of the trio, which falls apart after one last

calamitous prestation in Brussels. "I was convinced it was going to end in a

tragedy," says Smith. "Luckily, this incident killed the trio before we had

arrived at such extremes." Paradoxically, this brutal epilogue has undoubtedly

saved The Cure. Reduced to the Smith-Tolhurst duo, the group will be reborn

from its ashes in November 1982 with the 45 Let's Go To Bed - a pop singles

"voluntarily superficial", according to the singer - before filling its ranks

and finding the global success we all know. Gallup will rejoin the group later

for the recording of The Head On The Door (1985); he has been ever since then

one of the main pillars of the group. Tolhurst, thrown out in 1990, continues

to regard The Cure and its works well. "Even in the darkest periods, the group

has always had something positive. Our music was acting like an exorcism. We

wanted to feel better, to break through different stages." Smith approves:

"Many people thought I was going to kill myself after Pornography. I am

convinced, on the contrary, that I would have ended my life if we hadn't

recorded it. This record gives off a beautiful energy, simply because you can

hear three young people in anger. I find it wonderful that we could transform

so much distress into a creative act as vibrant as this. Without it, we would

have followed other paths, even more insane, like crime or vandalism. In my

whole career, Pornography is the only record that helped me grow. Thanks to

it, I became a different person, I finally had the feeling that I was changing

my skin. This record wasn't a monster; just a child difficult to bear."

A child

that grew up and even managed to have its own kids. Even in the Cure

discography, it remains a sort of oasis, where Smith comes back regularly to

replenish his inspiration. Besides, it is not a coincidence that the group has

recently released a double DVD, Trilogy, where they performed live and in

their entirety Pornography, Disintegration (1989) and Bloodflowers (2000) -

three albums cut, according to Smith, of the same material. Above all,

Pornography has slowly but surely impregnated mentalities. One can recognize

its inspiration in the more volcanic songs by Radiohead or the latest Sigur

Ros album. Or find it a place in posterity among the most liberated elements

of American rock, from Red House Painters to the Pixies passing by The

Rapture, who openly claim the influence of The Cure.

In

Asphyxiating Culture, Jean Dubuffet, in a reference to the poet and

philosopher Max Loreau, proclaims this dazzling aphorism: "Revolution means to

turn the hourglass upside down. Subversion is an entirely different thing; it

is to break it, to eliminate it." The Cure, not a thoroughly subversive group,

has never really broken the hourglass. But for the length of an album, it has

dared to throw it into doubt, up to flirting with madness. Under its

nihilistic appearance, punk remained a way of living in the world, because it

wanted to confront it; with Pornography, The Cure brought to its incandescent

point the word of those who would like to disappear from the world without

forcibly withdrawing from life. Charged with such an explosive substance, it

is no wonder that this record continues to enflame those who want to listen to

it.

A BIG THANKS to: Aria Thelmann

for the TRANSLATION.

(Cover)

(Cover)

(Cover)

(Cover)