Interview "The Talking Cure"

June 12, 2004 -

Guardian (UK)

Interview "The Talking Cure"

The Talking Cure

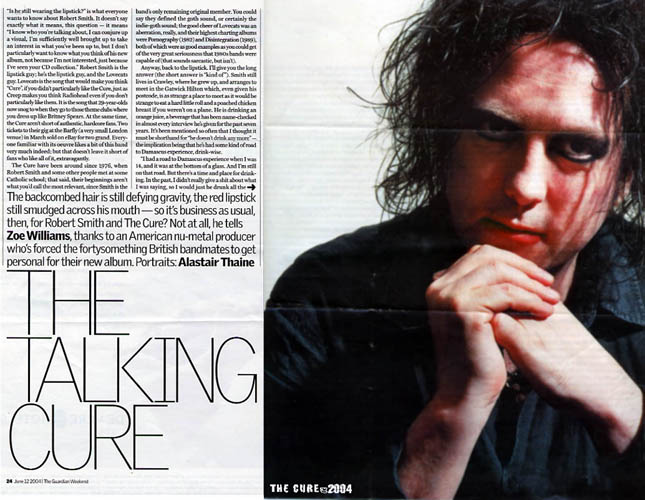

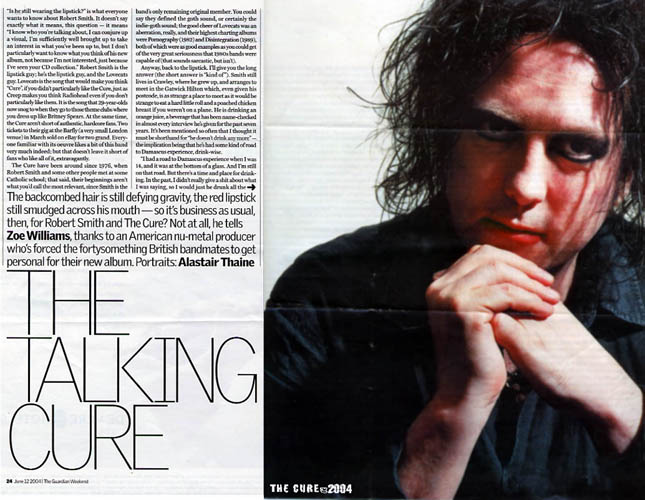

The backcombed hair is still defying

gravity, the red lipstick still smudged across his mouth - so it's business as

usual, then, for Robert Smith and the Cure? Not at all, he tells Zoe Williams,

thanks to an American nu-metal producer who's forced the fortysomething British

bandmates to get personal for their new album

"Is he still wearing the lipstick?" is what everyone wants to know about Robert Smith. It doesn't say exactly what it means, this question - it means "I know who you're talking about, I can conjure up a visual, I'm sufficiently well brought up to take an interest in what you've been up to, but I don't particularly want to know what you think of his new album, not because I'm not interested, just because I've seen your CD collection." Robert Smith is the lipstick guy; he's the lipstick guy, and the Lovecats guy. Lovecats is the song that would make you think "Cure", if you didn't particularly like the Cure, just as Creep makes you think Radiohead even if you don't particularly like them. It is the song that 29-year-olds now snog to when they go to those theme clubs where you dress up like Britney Spears. At the same time, the Cure aren't short of authentic, hardcore fans. Two tickets to their gig at the Barfly (a very small London venue) in March sold on eBay for two grand. Everyone familiar with its oeuvre likes a bit of this band very much indeed; but that doesn't leave it short of fans who like all of it, extravagantly.

The Cure have been around since 1976, when Robert Smith and some other people met at some Catholic school; that said, their beginnings aren't what you'd call the most relevant, since Smith is the band's only remaining original member. You could say they defined the goth sound, or certainly the indie-goth sound; the good cheer of Lovecats was an aberration, really, and their highest charting albums were Pornography (1982) and Disintegration (1989), both of which were as good examples as you could get of the very great seriousness that 1980s bands were capable of (that sounds sarcastic, but isn't).

Anyway, back to the lipstick. I'll give you the long answer (the short answer is "kind of"). Smith still lives in Crawley, where he grew up, and arranges to meet in the Gatwick Hilton which, even given his postcode, is as strange a place to meet as it would be strange to eat a hard little roll and a poached chicken breast if you weren't on a plane. He is drinking an orange juice, a beverage that has been name-checked in almost every interview he's given for the past seven years. It's been mentioned so often that I thought it must be shorthand for "he doesn't drink any more" - the implication being that he's had some kind of road to Damascus experience, drink-wise.

"I had a road to Damascus experience when I was 14, and it was at the bottom of a glass. And I'm still on that road. But there's a time and place for drinking. In the past, I didn't really give a shit about what I was saying, so I would just be drunk all the time. The only way I could get through a day of interviews was to have two drinks with every interview, so the person at the end of the day... well, I'd make sure it was someone who didn't speak very good English. I suppose the years go by, and you have to worry more and more. But also I'm more able to defend what I do. And also, I'm driving."

In other words, his behaviour has changed, his attitude has changed, the way he sees his work and his readiness to talk about it has changed. But his look hasn't changed. He still wears the lipstick, but not in that shouty, overapplied way; more in a rubbed-off, I've-had-me-lunch-and-haven't-reapplied way. It's no longer a statement, it's more just something he puts on and forgets about, like socks. And the hair... the hair is still jet-black, and back-combed, but again, it doesn't seem rebellious, it just looks lived-in and maybe a little slept-in. All in all, he makes you realise that the people whose appearances change the most are the ones whose outward garb changes the least; the clothing-continuity makes it that much easier to spot the physical ravages of time. We wrangle about why he dresses the same, seriously, for ages. He complains, casually, about having to put up with people saying, "Does your fucking hair look like that normally?", and I point out that he only has to put up with it because his hair does look like that, so maybe he's looking for the attention. "That whole thing about attention-seeking isn't really a part of it. I started growing my hair long and wearing make-up and stuff because I was at school and I wasn't allowed to."

"Well, then it was a rebellion against authority. But now you're not at school. Nobody cares how you look. Why still do it?"

"But the dress is just an outward manifestation of a rebellion against authority, and it's a lifelong rebellion against authority."

"Sure, but the authority doesn't exist that still cares. Why not rebel against an authority that exists?"

"Look, I get a much more extreme reaction when I have my hair really short. I look thuggish when I shave my head and wear big boots. I walk into a newsagent and people think I'm going to jump the counter. It's a much more extreme reaction."

"But you don't have to have really short or really weird hair. You could have regular hair."

"I married somebody who likes the way I look. If I changed my hair every year, and I reinvented myself in time-honoured pop fashion, I think understandably the person I'm married to would grow slightly sick of me."

"Does she still dress the same as when you met?"

"Yes! Give or take the school uniform, yes!" Grr! How can you give or take a school uniform?

I conclude two or three things from this conversation - Smith really isn't looking for attention. He seems entirely sincere both in his disdain for people who are attention-seekers, and in his insistence that he isn't one. His body language is self-effacing, and he mentions later that friends have commented on the way he gravitates towards corners and walls, which for a big (and famous) guy is an optimistic way to go unnoticed. He is truly and lastingly uxorious (she was at school, he was 18 when they met; now he's 45), which is such a warming feature when you're used to the hollow sounds of celebrities claiming to be and then having affairs a week later.

He found what he wanted to do, and made such a success of it, so early on, and with so much control and self-determination that I don't think he's ever been called upon to really defend a view. He'll defend it so far, and then, rather charmingly, go, "Well, it just is! That's the way it is!" But most of all, he really, really doesn't like change. He likes things the way they are. Later on, talking about his wife, Mary, he says, "I just struck lucky early on. I really enjoy what I do, and who I'm with and where I am. Having said that, I'm not really a person of habit, because what I do in my job is travel around the world and play concerts to people, and occasionally do very weird things. But my home life is full of the elements of normality that I enjoy, such as being in the same place with the same person. It's not a habitual thing, it's just that I can't think of anything else I'd rather do. I could do anything I wanted at this stage, I've got no children, I've got no ties, I could go anywhere and do anything, given the physical limitations of my body. But every year, I sit down and think, what shall I do this year? And I can't think of anything I'd rather do than what I do."

One of the most appealing things about this stasis is the extent and youthfulness of his enthusiasms. Asked which young bands he likes, he reels off tonnes of them; Mogwai, the Cooper Temple Clause, the Rapture, Interpol, Cursive, Thursday, Bright Eyes, Elbow . . . about 17 or 18 others. A lot of bands, and furthermore, bands he wouldn't be familiar with if he weren't taking as keen and full-time an interest as any teenage NME reader anywhere in the country. That a musician would love music, and take it seriously, is predictable enough - but to have been at it this long, and never fallen into the trap of thinking your generation was the best, of listening for plagiarism instead of flair, of defensively finding fault or of simply getting a bit tired . . . it's brilliant, really. It explains better than anything else why he's just made a new album, when for each of the past four, either he or the critics have been citing it as his last.

Smith says he hates cynicism, and its sidecar of irony. A lot of artists say that; normally, they mean "I hate it when critics are mean about me, what do they know?" Smith doesn't mean that. Which isn't to say that he has no critical faculty. He'll be plenty critical about his contemporaries - he still has space in his heart to say that Duran Duran epitomised everything he hated about the 1980s (although he's fine about Simon Le Bon . . . "I wouldn't say we were friends. But he's all right. I can chat to him"). And he has a frankly cock and bull theory about the Smiths, and how their influence on the era is overplayed because there's a media conspiracy, full of media people who liked them much more than anyone else did (mind, I would say that: I'm in the media, and I really like the Smiths).

There's something else that explains the new album, The Cure (self-titled because it expresses everything about them, "and anyone who doesn't like this just doesn't like the Cure") - Ross Robinson, nu-metal producer (he does Slipknot, among other things), and a very big Cure fan. Robinson made an awful lot of demands for this album - he wanted it to be recorded as though they were playing live together. Previously, the band, with its history of an ever changing line-up, had been used to Smith doing his bit, and the others doing theirs separately, finding their way through a funny little sound guy whispering "chorus" at them at predetermined moments. Robinson would have apoplectic fits at band members not putting their hearts into it. He made the whole business much more like some very young guys who had just met in a pub and decided to make beautiful music together, when for a long time, I think it would be fair to say, the albums have been made more like solo projects, with session musicians.

Smith claims he and Robinson never had a cross word about anything, apart from God. "Ross is a very firm believer in 'other' and I'm not. So those were the conversations where I'd get slightly exasperated." But Robinson also had some very personal aperçus about Smith and the way he operated, and projected himself. "Ross, when he first met me, was surprised at how unaware I am of the world around me. And on a very practical level, it's because I'm short-sighted. I don't wear glasses because I've found it's a very good defence mechanism. If I'm in public, I don't know if people are looking at me. But I can't actually see very well, I'm out of focus beyond my arm. And he thought I'd taken it too far, that I wasn't noticing the leaves on the trees. So I've started wearing glasses a lot more since I met him." There's a pause. He must think I look worried, because he adds hastily, "I always wore glasses to drive." It's a bit like Martin Amis, spending 25 years not smiling because he didn't want people to see his teeth; it sounds like a trivial, physical point, but you do wonder what it does to a person, to live the bulk of his adult life not seeing properly, just to evade the necessity of having to confront attention. It's another signal of his flexibility, as well, that he could adopt that modus operandi for so long, yet allow someone to call him on it, and then think, OK, maybe you're right, I'll change it.

The main feature of Robinson's way of working was that he'd have the band do one song a day, and before they started, ask Smith - the sole songwriter - to tell the others what it was about. "I thought, fucking hell, this is outrageous that I'm being asked to explain, and then I thought, no, I'm going to go along with this, the whole point of it is that it's supposed to be a different experience." So, he started to explain to the others, and then they'd discuss it, and they all became incredibly highly charged. There were tears and tantrums. The keyboard player, Roger O'Donnell, refused to engage with any of it, then had a screaming ab dab at Robinson, who laughed at him maniacally. Often, it would be workshopped for more than an hour before they'd even started playing. The example Smith gives is one song that is about bereavement: "I suffered a bereavement recently, and I was trying to put into a song, which I've never done before, the real sense of anger that I felt, rather than just the sadness and nostalgia and all that. I wanted the anger and frustration that comes with people you're close to, when they die." I get the impression that this is the easiest to articulate of many examples; that all the songs were a powder-keg, really, once the band started to talk about them.

Robinson is an American, and found the band's reserve very amusing, and by the sounds of things pretty alien and ludicrous at the same time. And the members of the band were these blokes in their 40s, who'd got through their entire acquaintance not talking about anything of emotional import, who'd suddenly been flung into a group therapy experience that they never for a second signed up for when they first learned to play the guitar (or whatever). It strikes me that it would make a brilliant film, seeing all these musicians who have been through decades of stoic rock, being mercilessly prodded by a maverick American producer, and unravelling all over the place, and then reforming to record another song, only to go through the same unfamiliar turmoil the next day. "Well, yeah, we did film it, actually," Smith recalls noncommittally, and I think he's wondering whether I'm taking the piss, but I'm not.

The changing line-up is a bit of an issue with the Cure. It is this that has earned Smith a reputation for "shark-eyed ruthlessness", if memory serves; kicking out members when they no longer suited him, carrying on regardless. This is almost wholly unfair, and is based on some court case brought against the band by keyboardist Lol Tolhurst after he was kicked out in 1988 - it's tedious, really, it has none of the meat of the fabulous Smiths case where the judge called Morrissey "devious, truculent and unreliable". Smith remains touchy about rumours of his control-freakery. "The last person I threw out of the group was in the mid-80s . . . This line-up has been together more than 10 years now. With this line-up we've outlived most other bands." "But do you find it difficult to cede control?"

"That's a very pejorative way of putting it, it assumes that control is important to me. It's not control. I just don't see the point of doing it someone else's way. I do this because I really enjoy it. If I'm going to write some words, and you go, no, I don't think that's good, I think, well you write your way and I'll write mine. And you're probably the same."

"I am. But I'm not in a band."

"Yeah, but if you ever interview a band and they say decisions are made democratically, they're lying. Most often, there are two characters who are abrasive and who'll be struggling, and there'll be two quiet ones who go along with it. Or there'll be one person, and everyone thinks, well, we're going to trust that person, which in this case is me, to make decisions that will be mutually beneficial. It's not a control thing." Oh, here we are again. It is! It doesn't mean it's a bad thing, but it bloody is a control thing.

When they really have made their last album (and there's no way of knowing yet whether this is it), I think we'll regret having underrated this band, at least for the past five or so years, maybe the past decade. Smith is very aware of this, though makes no big deal about it. In America, the Cure get much more attention and they have more cred; they play stadium gigs and headline at Glastonbury-scale festivals. Their record label is American; they haven't been signed over here since they split with Polydor. In the UK, the very fact of their having released their first album in 1979 and not had the grace to split up yet is enough to make people suspicious . . . how can they possibly have sustained their creative flair, where other bands part company? Well, either a) Robert Smith is a control-crazed maniac who keeps it going by kicking people out (he isn't; though he does like control); b) They're a busted flush anyway (they're not: they don't have a massive amount in common with what they sounded like on the first album, but there's just as much going on); or c) they can't stop: it's a compulsion, they're like some kind of musical magic porridge pot.

Actually, it's very unfair - they keep going because they still think they have songs to record, and a lot of people, faced with the songs themselves, agree with them, and buy them, and think they're great. I honestly think it's the 1980s look of the guy, coupled with the fact that he'll never sound like anything other than himself (like Morrissey, really, a similar victim of his longevity, until recently), that rings pastiche alarm bells; it's that, not any failure of creativity, that's given them the faintest tang of the novelty act. And it's a failure of imagination on the part of his compatriots. But he could also do himself a favour and stop wearing the stupid lipstick.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/ - thanks B.B. for the scan...