Elliptical Image Games

Interview / By: David Hepworth

September 8, 1979 - Sounds (UK)

Elliptical Image Games

Interview / By: David Hepworth

September 8, 1979 - Sounds (UK)

Elliptical Image Games

Interview / By: David Hepworth

There

were times when I was beginning to believe it. This interview took something

like two months to set up. We wanted to do it.

Everybody

wanted it done.

We were slated to travel to Port Talbot and chew the fat in the back of a van.

The gig was pulled. Alternative gigs were also unacceptable to one or other of

the parties. I had to go to a wedding. One of the band was ill. All of the band

were busy.

For weeks on end the whole thing appeared to have been forgotten and I’d reached

the stage where I wasn’t about to remind anybody, mindful of some of the other

pieces that had appeared in the comics under the thin guise of Cure

‘interviews’. I’d revolved round to the point of view that if The Cure wanted to

play elliptical image games, then they could play them with somebody else.

To borrow a favored technique of letter writers: "Just who the hell did they

think they were?" There were no signs that they were specifically burning up the

BMRB

charts, either on album or singles, and for every outright well over the top

rave review they got there’d be at least one more disaffected snipe at their

precocity and tendency to turn into household implements without adequate

notice. It was getting to the point where they had better come out of hiding

pretty sharpish

before everybody stopped looking for them.

It finally came together more through coincidence than anything else. I was

slated to attend a preview of

Quadrophenia in some

poncey

little flea pit on Wardour

Street and the PR man announced that The Cure would also be attending so why

didn’t we make an evening of it, go for a meal afterwards, mutter on to the

magnetic tape and get the thing done and dusted once and for all. Fine.

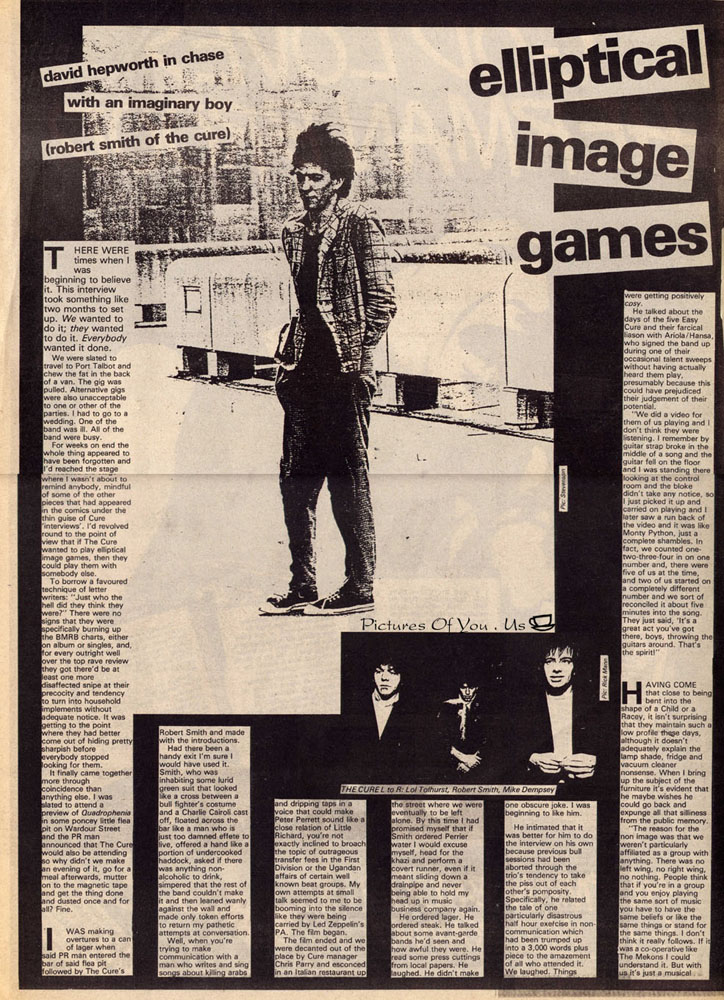

I was making overtures to a can of lager when said PR man entered the bar of

said flea pit followed by The Cure’s Robert Smith and made with the

introductions.

Had there been a handy exit I’m sure I would have used it. Smith, who was

inhabiting some lurid green suit that looked like a cross between a bull

fighter’s costume and a Charlie

Cairoli cast off, floated across

the bar like a man who is just too damned effete to live, offered a hand like a

portion of undercooked haddock, asked if there was anything non-alcoholic to

drink, simpered that the rest of the band couldn’t make it and then leaned wanly

against the wall and made only token efforts to return my pathetic attempts at

conversation.

Well, when you’re trying to make communication with a man who writes and sing

songs about killing Arabs

and ripping taps in a voice that could make Peter

Perrett

sound like a close relation of Little Richard you’re not exactly inclined to

broach the topic of outrageous transfer fees in the First Division or the

Ugandan affairs of certain well known eat groups. My own attempts at small talk

seemed to me to be booming into the silence like they were being carried by Led

Zeppelin’s PA. The film began.

The film ended and we were decanted out of the place by Cure manager Chris Parry

and ensconced in an Italian restaurant up the street where we were eventually to

be left alone. By this time I had promised myself that if Smith ordered Perrier

water I would excuse myself, head for the

khazi

and perform a covert runner, even if it meant sliding down a drainpipe and never

being able to hold my head up in music business company again.

He ordered lager. He ordered steak. He talked about some avant-garde bands he’d

seen and how awful they were. He read some press cuttings from local papers. He

didn’t make one obscure joke. I was beginning to like him.

He intimated that it was better for him to do the interview on his own because

previous bull sessions had been aborted through the trio’s tendency to take the

piss out of each other’s pomposity. Specifically, he related the tale of one

particularly disastrous half hour exercise in non-communication which had been

trumped up into a 3,000 words plus piece to the amazement of all who attended

it. We laughed. Things were getting positively

cozy.

He talked about the days of the five Easy Cures and a brief affiliation with

Ariola/Hansa

who signed the band up during one of their occasional talent sweeps without

having actually heard them play, presumably because this could have prejudiced

their judgment

of their potential.

"We did a video for them of us playing and I don’t think they were listening. I

remember my guitar strap broke in the middle of a song and the guitar fell on

the floor and I was standing there looking at the control room and the bloke

didn’t take any notice, so I just picked it up and carried on playing and I

later saw a run back of the video and it was like Monty Python, just a complete

shambles. In fact, we counted one-two-three-four in one number and, there were

five of us at the time and two of us started on a completely different number

and we sort of reconciled it about five minutes into the song. They just said,

‘It’s a great act you’ve got there, boys, throwing the guitars around. That’s

the spirit.’"

Having come that close to being bent into the shape of a Child or a

Racey,

it isn’t surprising that they maintain such a low profile these days, although

it doesn’t adequately explain the lamp shade, fridge and vacuum cleaner

nonsense. When I bring up the subject of the furniture it’s evident that he

maybe wishes he could go back and expunge all that silliness from the public

memory.

"The reason for the non image was that we weren’t particularly affiliated as a

group with anything. There was no left wing, no right wing, no nothing. People

think that if you enjoy playing the same sort of music you have to have the same

beliefs or like the same things or stand for the same things. I don’t think it

really follows. If it was a co-operative like the

Mekons

I could understand it. But with us it’s just a musical thing. I don’t really

socialize with Mick and Lol. I never socialize with anyone really."

It’s amusing the way that few mentions of The Cure go by without someone

remarking on their relatively comfortable backgrounds, their ‘middle class’

roots, as if the overwhelming majority of great bands came from some fictional

slum city and any musician who happened to be born outside of its perimeter is

somehow best viewed with suspicion until he has proven himself as dull and

boorish as everybody else. The fact that most of these observations emanate from

university educated rock critics makes the whole charade even more laughable.

Although Smith would like to emphasize that he actually attended a comprehensive

school rather than the public school of other fond imaginings, he treats the

whole argument with a contemptuous puzzlement.

"People tell me that deprivation breeds good music and all that but quite often

real poverty causes desperation more than anything else, a kind of blind belief

in what you’re doing which is perhaps a good thing or sometimes it’s a bad

thing. But I’ve always been materially secure if not mentally secure. People

used to come up to us when we were looking for a contract and say ‘I can give

you this or give you that’ and I wasn’t really interested because it didn’t mean

that much to me. ‘The other two will pass as working class. Mick worked as a

porter in a mental hospital and Lol worked in an ink factory, but whether that

makes them any more valid to play music I don’t know. Why do you have to be born

in poverty to know what’s going on? Quite often I find it’s the other way round.

I you don’t have to fight for you existence every day you can maybe take time

out to think. Whether you do anything about it is a different matter."

"It’s all very facile anyway, the whole life style. Going on the road is

supposed to be the essence of the life style, getting pissed every night,

smoking as much as you can and pulling ‘dodgy boilers’ or whatever they call

them. It all sounds really great. But I’ve been going out with the same girl for

about five years now, so I’ve never really been involved with the whole

one-of-the-lads

scene and things like that. I haven’t really got that group sensibility, I

suppose, of belonging or things like that. I don’t feel the need to expose

myself to anyone. I don’t really open up because I used to a lot and I ...

there’s so few people I’ve met that I can get on with and that you can trust

that I don’t really see it’s worth it."

"When you’ve been going out with somebody a long time and there’s a choice

between staying in and watching the

telly

with them and going down the pub, then you’ll stay in. It’s like The Undertones;

their songs are virtually all about getting girls and getting girls is the

ultimate. So, when you’ve got

a girl, what happens then?"

‘Boys Don’t Cry’ came on like it was a simple stab at the charts worthy of The

Undertones at their most gloriously naive. How did he react to its lack of

success?

"It’s like commentators in cricket", he laughs, "They always say, ‘Oh, he’s

doing really well’ and then he gets bowled out. We were advised not to bring it

out because of the fact that it was a pop single and it would be much better if

we brought out something that was less commercial but more ‘artistically

viable’. ‘Boys Don’t Cry’, ’10.15’ and ‘Accuracy’ have always been my favorite

songs out of all that initial lot. I’m glad it didn’t make it in a way because

then the people who’d been saying we shouldn’t put it out would then have turned

round and said you’ve gotta

give us another one like that one."

"The subject matter has changed drastically in the new songs. The songs on the

album were basically about a relationship. They were one to one, whereas now

they’re very... they’re just taking a broader range of subjects, I suppose,

things that affect other people, not only me."

Robert Smith claims so little for rock and roll that you wonder if he deserves

it. But he works in left field whether he likes it or not and is doing his best

to prove that you can fashion exploratory pop without coming to grief at the

feet of appropriated radical ideas and extraneous bullshit.

"It’s ridiculous. You put out an album that’s greeted with some measure of

critical acclaim and you’re immediately in a position where people should listen

to you. I never even expected ‘Killing An Arab’ to be recorded, and you get

people going into the motives an demeaning and all that, and it would be so easy

to pick something up, there’s numerous little ploys that people use which are so

transparent and they’re expounded every week in the press. It might be

flattering to know that people want to know what you think, but I don’t really

see myself as one of the top three original thinkers in the world today, so I’m

not in any position to expound my philosophy of life."

Robert Smith left the sixth form and fell right into The Cure. He has had two

jobs. He has been a gardener and he has been a postman.

"I had five weeks as a gardener on an industrial estate in the height of summer

and they were five of the happiest weeks of my life. Compare that to a Wednesday

in Leeds and its raining and you’ve got to go on stage at the F Club and there’s

a bunch of rather unsavory looking people barracking you.

Is it better than working?"

"It is

better than working."

Don’t like peas? Be like Robert Smith, order spinach.