Interview - Stuurkunst - Pink Pop 86

May

17, 1986 - OOR (Netherlands)

(Translation below)*

Interview - Stuurkunst - Pink Pop 86

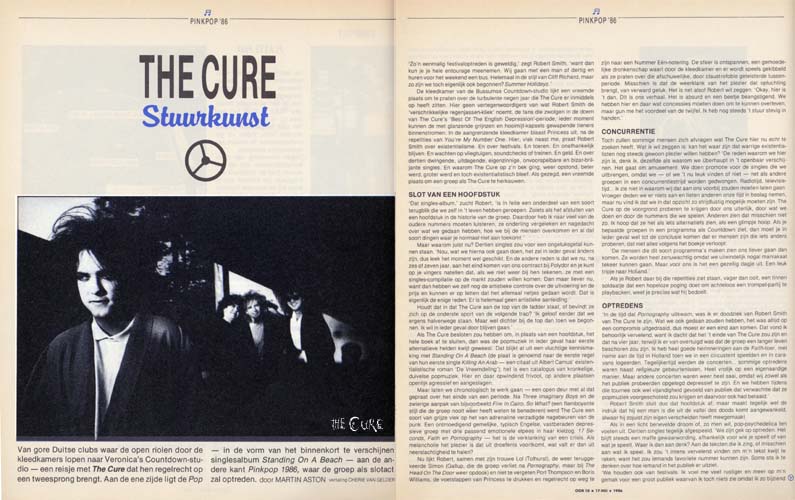

From filthy German clubs, where the sewers are running through the dressing rooms to Veronicaís Countdown-studio; this journey brings The Cure to a crossroad. One side represents Pop, the new singles-album ĎStanding On A Beachí and the other side Pinkpop 1986, where the group will be the final act.

This one-off festival is great, says Robert Smith, cause then we get to take our entire entourage with us. There will be about 30 people on our hired coach for the weekend. Itís very Cliff Richard-like, but thatís how we started, isnít it? Summer Holidays.

The dressing room of the Countdown-studio at Bussum seems a strange place to be talking to about the turbulent nine years of The Cure. Robert Smith is happy to see none of the, what he calls, Ďfrightful raincoats-peopleí; the fans who wallow in the Ďbest of the depressioní period. Any minute the teenagers with shining smiles and high haircuts can come charging in. In the room next to theirs Princess is taking in a break after her rehearsals for the song Ďyouíre my number oneí. But here, next to me, Robert Smith talks about existentialism. And festivals. And touring. And about staying independent. And about waiting for planes, sound checks or trains. And money. And about thirteen amazing, provocative, unpredictable, bizarre and brilliant singles. And why The Cure fluked, got up again, became better and bigger and still stayed very existentialistic. Like we said, it is a strange place to be interviewing The Cure.

The closing of a chapter

Robert Smith sighs: Ďthat album is a sort of looking back on things weíve created ourselves. Itís like closing a chapter in the history of a band. Therefore I had to listen to a lot of old songs again, compared them and thought about what weíve done, how people experienced our music and all those things that we didnít have time forí.

But why now? Thirteen singles, itís an unlucky number. ĎWell, whatever we will be doing afterwards, it will be different, so the timing seemed right. And another reason is that after six or seven years, our contract with Polydor is ending, and you can bet on it that if we donít sign a new contract, they will be releasing a singles-album. So we would rather do it know, while we still have artistic control over the album, the price, and make sure that itís done in a good way. Thatís the only reason. Thereís actually no artistic reasoní.

Is the Cure standing on top of the stairs or are they at the bottom of new stairs? ĎI believe we are somewhere in the middle, but closer to the top than we were at the beginning. Anyway, we will continueí.

If the Cure would have decided instead of closing a chapter, to close the entire book, than popmusic would have lost its last alternative heroes. Weíve just had a brief chance to see Standing on a Beach (named after the opening line from Killing an Arab, a quote from Camus existentialistic novel LíEtranger), but it is a catalogue of diabolic popmusic. At certain times very frivolous and sometimes very aggressive and down.

But letís look at things chronologically; itís an open door with all that talk about closing a chapter. After Three Imaginary Boys and the flirty approach like Fire in Cairo, So What? (a very flamboyant style which they have never achieved again), The Cure became a sort of grey spot on the adrenaline-satisfied Punk scene. A very demoralized, very British, holding on the depression, band who have made three emotional albums. 17 Seconds, Faith, Pornography, all representing a crisis. If melancholy is the pleasure that one derives from sadness, then what is to come forth from depression?

Right now, Robert Smith, with buddy Lol (Tolhurst), Simon (Gallup, who left the band after Pornography, but resurfaced with The Head on the Door), and lets not forget Porl Thompson and Boris Williams, are stepping into the footsteps of Princess and are on their way to a number one hit. Thereís a relaxed atmosphere in the dressing room, while everybody gets a little drunk and starts bickering when they talk about the dark intermediate period. Maybe thatís a result of the relief and confused happiness. Itís as if Robert is saying: Ďthis is it, this is our story; itís absurd and a bit frightening. Weíve had to make concessions in order to survive, but give me the benefit of the doubt. Iím still in controlí.

Competition

Still, some will be wondering what The Cure is doing here. What I mean is: is it true that the confused existentialist still want to have fun? The reason weíre here is, I think, the same reason as to why we still appear in public. Itís about entertainment. We promote the singles we release because weíre competing with other bands, whether we like it or not. Airplay, television-time.. I donít see why we should ignore it. In the old days we didnít care and we let other people take up our time, but now, I think, we have to compete. The Cure should try to be in the spotlights because of how we look, what we do and the songs we play. Other people might think otherwise. I hope the consider us something alternative. A sparkle of hope. If you look at certain bands on Countdown, you have to realise that theíre are people who like things a bit different, who donít follow the same path. ĎPeople who make this kind of programs donít really like us. They get nervous because we act like maniacs. But to us itís a day out. A journey to Hollandí.

When you look at Robert at the rehearsals: a tin soldier trying to playback a trumpet solo, you know exactly what he means.

Gigs

ĎWhen we released Pornography I was sick of being Robert Smith. Whatever we would have done, it would have been a compromise, so we had to end it. I hated it, because I thought it would be the end of The Cure after four years, while I knew that we could have lasted longer. My memories of the Faith tour are great, especially when we weíre playing in that circus tent in Holland and slept in trailers. At the same time the concerts wereÖalmost religious events. They were very happy in a certain way. But others were boring because both the audience and we were trying to be very depressed. And we also experienced a lot of hostility; certain people in the audience were expecting pop songs and had paid for themí.

Robert Smith closes a chapter, but he seems as a man who has been in the valley of death and witnessed his own dead. Itís like a dream under influence of alcohol, very psychedelic. Thirteen singles were played at once. ĎWe love gigs. Itís still a weird feeling depending on who you play for and what you play. Iím thinking about the lyrics I sing or perhaps about what Iím playing. I would hate to forget the lyrics, because it could be someoneís favourite song. Sometimes I think about how certain people in the audience look.

We also like festivals. I feel much more at ease in front of a large audience which I donít see because Iím so short-sighted. If you would invite ten people and I would have to pick up my guitar and start playing, I would be very nervous. But when itís more than a thousand people, I relax.

I liked playing in clubs; it smells, itís hot and the crowd is rude. But Iíve never been to festivals, unless we had to play ourselves. I canít image going to one, because I donít like the idea of being with a huge crowd with whom I share nothing but a common interest for the bands on stage. Who else are playing at Pinkpop? Well, Jesus and Mary Chain have cancelled so that leaves Claw Boys Claw, Cock Robin, The Waterboys, The CultÖ AAAAAAARGH!í

Latest news

ĎWeíve remixed Boyís Donít Cry because we had to find a song that could be played on the radio. It had to be one of the older ones, because theyíre known to people. But weíve never made a video for that song and I didnít felt like play backing that crow-like voice that I used before. My singing is much better now And if you would take that song out of its original context it would be very feeble. The album contains the old version, but on the single itís modernised, also because of the competition. If I would have thought that everybody knew the Cure, it wouldnít have mattered, because everybody would have recognised the old song. But it isnít like that: certain people could think Ďthat sounds like crapí or Ďgod, that voice, what happened to this guy?í

Looking back part 1

If I imagine that I would be here as a fifteen year old and looking at myself like I am now, I probably think: Ďgood, he stayed a normal guyí. And if I would like that fifteen year old I would probably say: Ďyou bastard, youíre so thin!í

Looking back part 2 the singles

Killing an Arab

When I listened to this song for the compilation is had been a very long time

since I last heard it and I was surprised at how lanky it sounded. I couldnít

believe it. It had just worn out. It didnít sound like it was in my mind, but

we had to start somewhere and it was the best choice because it made us rather

famous. Itís based on existentialistic problems within the limits of a pop

approach in two and a half minutes. At that time it was rather unusual. People

didnít know whether to believe it or not or whether we were all philosophy

students.

Boys

Donít Cry.

It was an attempt at writing a pop song without making pop music, although it is

my idea of what pop is. When it was released it was considered the perfect pop

song, which it wasnít because it sold less than any other Cure song.

Jumping Someone Elseís Train

It was a reaction to the Mod revival. It was a success, although people at NME

will tell you that they have never been part of it. But we were old news

because of the revival and this was our way of getting back at all those people

who all of a sudden decided that they always loved The Who.

A

Forest

Just like Killing An Arab it made us a bit famous, especially here in Holland.

It describes an experience of me when I was 12 or 13. At first we wanted to

release Play for Today as a single, but we thought it would be too obvious, so

we decided to release A Forest to make it a bit obscure.

Primary

We didnít want to release a single for the Faith album, because it wasnít that

kind of album, but we had to, for the same reasons as now with Boys Donít Cry.

We had to get the attention drawn to the album and Polydor wanted a single that

could be played on the radio. And of all the songs, this was the least

suitable. Itís like a lost paradise, like a forest. I went through a very

melancholic period.

Charlotte Sometimes

I got the title from another book, from Penelope Farmer. Even now I rather fall

in love with a girl from a book than a real girl. Theyíre always perfect and

they never change. We were very proud of it when it was finished and I still

think itís one of the best things weíve ever done.

The

Hanging Garden

I used to write a lot of songs when I was feeling a bit weird. I had a lot of

naturalistic, antique of religious images in my head and I used to combine

animals or wild sex with religion. Everybody knows you canít combine religion

and sex! Very confused.

Letís

Go To Bed

And this is were religion got kicked out the door! It had a double meaning. I

meant letís go to bed like Iím bored here, letís go to bed Ė but

separate beds. But nobody understood it that way. We never contradicted it

because it helped to break down the myth that The Cureís only gloomy and dark.

The

Walk

This is a true story. It happened to me when I was hanging out at a big lake

near my house. The Howling woman was a woman who was walking her dog.

It happened at about two oíclock in the morning and I wrote the song when I got

back home.

The

Lovecats.

I was convinced we had to make a song that sounded like a Disney-soundtrack. I

wrote the lyrics in Paris and they donít mean anything. The ideaís from a book

in which a guy puts all this cats in bags and throws them in a lake. At first

that was the opening line, but I felt I couldnít sing that in a pop song.

Although itís one of the least emotional things weíve done, itís one of my

favourites. But I canít imagine us doing something like this again.

The

Caterpillar

This is again a stereotypical image, like Boys Donít Cry. Itís a typical

relationship song. Itís not about anybody I know, but about what could happen.

Inbetween Days

Iím very attached to that song. I think itís the best single weíve made.

Everything was right: the songs, the people who were working on it. It was al

very easy. Actually it was not about days, but about nights, but I didnít want

to talk about nights. Theíre were already enough nights on The Head on the Door.

Close

To Me

Itís about claustrophobia, but not about the physical form. Itís about wondering

what you are doing in that room with those sorts of people. Something about

that.

A very BIG THANKS to: ANKE for the TRANSLATION.