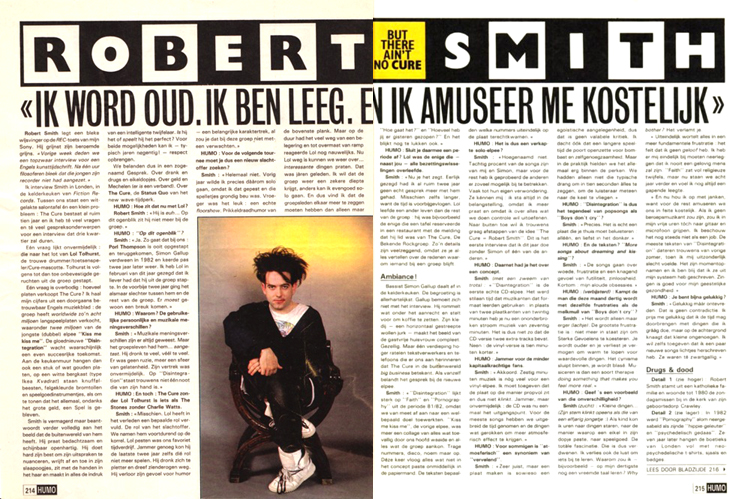

I’m getting old, I feel empty, and I’m having so much fun” (Interview - 4 pages)

4/1989 - Humo (Belgium)*

(Translation below)

I’m

getting old, I feel empty, and I’m having so much fun”

(Interview

- 4 pages)

HUMO (Belgium) April 1989:

“I’m getting old, I feel empty, and I’m having so much fun”:

Robert Smith puts a pale finger on the REC-button of my Sony, with his famous grin on his face. “Last week, we did a very deep interview for an English art magazine. After an hour of philosophizing, it turned out that the guy hadn’t turned on his recorder.”

I’m interviewing Smith in London, in the basement kitchen of Fiction Records. Between us, there’s a white table and one small problem: The Cure has already existed for 10 years and I have too many questions and too many conversation topics for an interview that can only last 45 minutes.

One question seems inevitable: what’s the case with Lol Tolhurst, the loyal drummer/keyboard player/Cure mascot. Tolhurst has stepped out of the band according to a till then unconfirmed source. One question seems unnecessary: how many records The Cure sells. I get my numbers out of a reliable English music magazine: the band has sold about 8 million LP’s worldwide, and 2 million from their last LP, KMKMKM. An equally successful future lies ahead for the brand new Disintegration. On the kitchen wall hang a couple of gold records, in a white cupboard there are some teddy bears, spinning tops and toy instruments, as if to show that it’s all still a game, despite the big money.

Robert Smith has lost weight but other than that, he perfectly matches the image the outside world has about him. He talks thoughtfully and in all openness it seems. He tries very hard to nuance what he says, rubs his sleepy eyes now and then, puts his hands in his hair and makes it look in every little detail as if he is a very intelligent but doubtful person. Is he really, or does he just play it perfectly? For both, I can, typically for the nineties, respect him. We end up in a so-called ‘conversation’ – about drinks, drugs and acorn nutshells. About money and Mechelen (a Flemish city), yes there’s a connection! About The Cure, the Status Quo of the new wave era.

HUMO: What’s up with Lol?

Robert Smith: “He’s uhm…. At this moment, he’s no longer in the band.”

HUMO: At this moment?

Smith: “Yes, that’s the way it goes with us: Porl Thompson once quit the band and then came back, Simon Gallup disappeared in 1982 and only returned 2 years later. I told Lol in February of this year that I would rather have him to leave the band. In the past two years, it became worse and worse between him and the rest of the band. It had to break apart!”

HUMO: Why? The usual personal and musical differences?

Smith: “Musical differences have always been there. But living in a band had… affected him too much. He drank too much – way too much. There were no fights, just an atmosphere of apathy. His departure was inevitable. There is not one note on Disintegration that comes from his hands.”

HUMO: And still: The Cure without Lol Tolhurst is somewhat like The Stones without Charlie Watts.

Smith: “Maybe. Lol played a certain role in the past - the role of the victim. We constantly criticised him. Bullying Lol was our favourite thing to do in our spare time. Sadly enough, he couldn’t even fulfil that part anymore in the last 2 years. He drank so much he slowly sunk into something unrecognisable. He lost his sense of humour, a very important part of his character, although you wouldn’t immediately expect that with this band.”

HUMO: For the next tour, you are forced to look for another victim?

Smith: “Not at all. Last year, that was exactly the reason why I wanted to go solo, because I was fed up with all of those games and all of that bullying. It used to be fun, a real floorshow; top-shelf barbed wire humour. But after a while, it had more to do with a constant attack and the worst thing was that Lol didn’t even react to it anymore. Now Lol is gone, we can talk about interesting things again. It’s been years since that was possible. I want the group to get a certain depth; otherwise I might as well go solo. And so I think the band members have to have more to say than just ‘how are you’ and ‘how much did you drink last night?’ And it seems to work as well!”

HUMO: Do you put an end to a certain period this way? Lol was the only one, except for you who survived all the personnel changes along the way.

Smith: “Now you mention it. To be honest, I hadn’t really had a civil conversation with him in the past two years – maybe even longer, because time has flown by. Lol lived a different life compared to the rest of the band: for example, he was the only one who reserved a table in a restaurant by saying that he was a member of The Cure, the famous rock group. Details like that do say a lot, because they tell you everything about the reason why a person stays in a group.”

Pleasure !

Bassist Simon Gallup enters the basement. He and Robert greet each other like two best friends would. Gallup doesn’t interfere with the interview. He messes around in the kitchen and offers to make coffee. His clothes, a horizontally striped woollen dress completes the image of the housewife. An intimate feeling. But one floor above, the phones and word processors are busy; reminding us of the fact that The Cure means big business in the outside world. Smoothly, the conversation leads us towards the topic of the new album.

Smith: “Disintegration sounds a lot like Faith and Pornography, from the 1981-1982 era, cause we worked towards a certain goal from the beginning. KMKMKM, the last records were more of a collage of everything that was in our heads and what the band was able to play. Slow songs, disco, you name it. This time, everything that didn’t fit the concept was thrown away. Ultimately the lyrics decided which songs made the record.”

HUMO: It’s more a disguised solo album then?

Smith: “Not at all. 80 % of the songs are from Simon and I, but for the rest of it, I tried to get the others involved as much as possible, which surprised them a lot. They know me: I’m always in the spotlights, because I talk more and I want to have control about everything we do. I want to get rid of the idea that The Cure = Robert Smith. This is the first interview I’ve done this year without Simon or one of the others.”

HUMO: Earlier on, you talked about a concept.

Smith: (with some pride) “Disintegration is the first real CD-LP. It was about time the musicians learned to use this format: instead of two twenty-minute sides of an LP, you now have a seventy-minute stream of music without interruptions. So it’s not that the CD version contains two extra tracks. No, the vinyl version is ten minutes shorter.”

HUMO: A pity for the less wealthy fans.

Smith: “Agreed. But sixty minutes of music is still a lot for a vinyl version. I have to admit that the LP is stuffed to the maximum that way and doesn’t really sound good. We just started thinking in CD terms, that’s why. For the most part of the songs, we took our time really well and stretched things out to get a more atmospheric effect.”

HUMO: For some, ‘atmospheric’ is a synonym for boring.

Smith: “Very true. But making a record is a very egoistic thing, so that’s not a valid criticism. I also thought that more running time on the CD would open up the door to a bombastic sound and self-satisfaction. But in the end we managed to contain it pretty well. Only, we didn’t have that typical urge to tell everything within ten seconds, to grab the listener by the throat instantly.”

HUMO: Disintegration is the opposite of pop songs like Boys Don’t Cry then?

Smith: ”Exactly. It’s really an album you have to listen to at home: alone, and preferably in the dark.”

HUMO: And the lyrics? “More songs about dreaming and kissing”?

Smith: “The songs are about anger and frustration and a gnawing feeling of futility and meaninglessness. My old, returning obsessions.

HUMO: (surprised) Does the man that turns 30 this month have the same frustrations as the teenager from Boys Don’t Cry?

Smith: “It only got worse (laughs). The biggest frustration is: not being able to feel strong emotions anymore. You get older and you lose the ability to really get excited for valuable stuff. Cynicism enters your world and you get numb. Making music is like therapy then: doing something that makes you feel more real”

HUMO: Can you give an example of that indifference?

Smith: (sighs) “It’s little stuff (all of a sudden his voice sounds like an 11 year old). As a little child, I could stare for hours at stuff; at the way an acorn nut fits perfectly in a nutshell, at toys. Total fascination. That has disappeared. I also lose the lust to keep learning. Why should I learn a foreign language when I’m 30? Why bother? That feeling paralyses you. Eventually everything has its roots in a more basic frustration: the fact I don’t have a belief. I had to accept the fact that I would never be a religious person. ‘Faith’ was full of religious doubt, but we’re 8 years further now and I still feel the gaping emptiness. And now I stop whining, cause besides that we’re having so much fun. If I wouldn’t be a professional musician, I would still grab my guitar and microphone in my spare time. I still don’t consider it as a job. Most of the lyrics on Disintegration are dated last summer when I felt extremely miserable. They describe moments and I’m glad that I got rid of them by writing about it. Singing is good for my mental health.”

HUMO: You’re almost happy?

Smith: “ Happy but unpleased. That’s not a contradiction. I count myself lucky that I can spend my time doing the things I like to do, but in the background the small unpleasant feelings gnaw. I even want to admit that I rewrote a couple of the new songs, they were too pessimistic.”

Drugs and death:

Detail 1: (see above) Robert Smith comes from a very catholic family and went to the Sunday masses in Crawley until 1980.

Detail 2: (see later on) In 1982, Pornography was criticized as being hippie bullshit and psychedelic babbling. Seven years later, the boutiques in London are full of neo psychedelic t-shirts, scarves and signs.

Smith: “It’s funny how the whole acid house boom has passed me by. You really have to be a frequent visitor of a disco for that. Not my cup of tea. Here at Fiction they are very busy working with that though. I think it’s good that smaller groups and smaller labels risk their chance again: it reminds of the punk era. On the other side I loath the snobbism and elitism of it all: ‘I was already acid when you were still new wave’ - that stuff. In fact it’s all as small as the ska revival where I wrote an angry song about: Jumping Someone Else’s Train. Now I read articles everywhere about the new ska revival. Despicable. At this rate, we’re having 5 revivals every year. I’m probably old fashioned, but I like music that’s not limited to a certain time. And I keep cultivating my hate for music that I can’t stand. Even if the Pet Shop Boys would make good music, I still wouldn’t buy an album of them. Cause I hate Neil Tennant.”

HUMO: Was Pornography really a psychedelic album?

Smith: “I suppose it was. Everyone that was in the band back then had an older sister or brother. We grew up listening to the music of an older generation. We listened to bands like Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Captain Beefheart and Interstellar Overdrive from Pink Floyd. Especially Interstellar Overdrive (laughs).”

HUMO: Pornography was also a real drug album.

Smith: “Absolutely. That whole period of my life was about physical and mental experiments. The sky was the limit.”

HUMO: How did you live back then? Didn’t you have planes to catch, shows to perform?

Smith: “I was quite young, about 21 years old, and blessed with a fabulous stamina. When I think about all the things I did in the past 10 years, I should be in a wheelchair. In 1982, I had a complete mental and physical break down. I drank, I was popping pills and in the meanwhile I was working insanely with The Cure and as a guest guitar player for Siouxsie and the Banshees. I never fully recovered from that: I notice that when I play soccer (laughs). We lived a double life. We played soccer after the soundcheck and hardly realised when we had to go on stage. If I would try to do that now, it would go horribly wrong. I also recover much slower than I did. I used to have the worst hangovers but at least I had fun the night before. Now the hangovers are so heavy, I wished I wouldn’t have had that much fun (laughs). Simon is going through the exact same thing. All my friends seem to be tending towards complete soberness. That’s why things went wrong with Lol Tolhurst. He just continued. A latent wish for death, I think. But his girlfriend told me he’s been drinking less lately. Maybe the shock of the break up will get him sort of stable again. He needed that. Now I know why I did all of that stuff those years. I wanted to test myself, see how far I could go, and see how it would feel to be death. I wanted to know if my so-called love for death was real. And one night I realised I absolutely didn’t want to die. I was scared and I immediately knew that it was better to take it slowly from then on.”

Cure and money:

HUMO: Something different now. At first, why didn’t you want to play in Vorst National this year?

Smith: “Normally we try never to play the same venue twice, but in Belgium it’s crazy to find another decent venue. The only alternative was that damned vegetable market hall in Me-che-len (he pronounces it accurately). In the Netherlands, we get lots of criticism because we avoid Amsterdam and Rotterdam and only want to play in the ice hall of Heerenveen. And apparently nobody lives in ‘Herrenvean’. People who live in capitals are hopelessly spoiled. It’s very hard to get a crowd in Brussels or Rotterdam excited. Now you can say that many people in the Netherlands will have to travel far to see us play, but by that, you at least avoid the people just being there cause it’s a coincidence we happen to play there. I’d rather play for a small, enthusiastic crowd than to a sold out tame reacting venue. It’s a bit egoistic, I know.”

HUMO: Is it fair to charge people 800 hundred Belgian franks (20 USD) for a concert in a hall with hardly a better acoustic than an average train station hall?

Smith: “Maybe not, but don’t forget that a venue like Vorst National doesn’t sound that good as well. The only alternative is playing 3 or 4 shows in smaller venues, but that way we can keep touring. The original idea was to tour six weeks. Now we already made that many exceptions that we’ll be touring 13 weeks. The rest of the band is starting to moan, me as well actually.”

HUMO: Do you want to gain as much money as possible in a short period?

Smith: (sounds like that 11 year old boy again) “I always think back of that night in London when I wanted to see John Martyn perform. Not really the most popular artist in the world, but nonetheless The Mean Fiddler was sold out and I stood at the door without a ticket. I was so furious. I almost started to hate John Martyn. Why couldn’t he play in Hammersmith Odeon so all his fans could see him? That’s what I think about when I’m playing to 12 000 people in a venue that as a 16 000 people capacity. Better that than playing in a venue for

10 000 people with 2000 fans out on the street having to pay insane prices for a ticket on the black market. Those 2000 people are going to dislike the group and I don’t want that to happen. I admit we rarely play in ideal conditions, but often we have no other choice. In Germany, in Essen there’s the worst concert venue in the world: all grey, like you’re playing under a cloudy sky. Frustrating, certainly when you played in a beautiful amphitheatre in Italy or the South of France a week earlier, where everyone is dressed in comfortable summer clothes and the moon gives the most beautiful light. Those are nights never to forget.”

HUMO: So it’s not about the money?

Smith: “No, cause it would be a lot cheaper to just visit 3 countries and play 5 stadium concerts there. The business side of this tour is frightening. We’re spending more than a million pounds. With a little bit of luck, we can gain as much from it as well. That’s because we also go to Austria, Greece, Yugoslavia and Hungary and because we swore off travelling by plane. In Hungary we will be playing to 2500 people and we don’t even have the guarantee we will be paid. Careful though: we’re no saints. We never toured with loss and we’re not planning to cause that’s absolutely useless. I can’t expect the group to pay money to tour. And why should we be making loss to be credible? Even the most avant garde experimental artist likes to make his living.”

HUMO: How naïve or clever are you business-wise?

Smith: “This tour I control from A to Z. I chose the venues, I take care of every little detail about promotion, posters, and so on.

HUMO: Why? Have you ever been deceived?

Smith: “With the last tour, several practical things went horribly wrong. I got very angry then. This time I want to do everything myself. If something goes wrong, I can only scold myself. The Cure has never had a real manager. I’ve always taken care of everything that concerned money. Almost all of the profit goes back into The Cure. We don’t own much, but we have control of everything we do. This tour, for example, is financed with our own means. That’s the money we could otherwise be using to buy sport cars. It may sound weird, but money has always been important for us. When you neglect the financial side of things, it’s guaranteed to go wrong with the artistic side of the band. A lot of bands seem to think they can leave the management of the band up to other people so they can fully concentrate on their lives as an artist. But then you open the door for deception, bad management - you name it. Look at it this way: one day a bill comes in the post, which you aren’t able to pay. What do you do? You search for someone who can lend you the money. From that moment on, you’re a slave to the will of the record company or whoever lent you the money. The Cure works with open books: how else do you think we managed to do it for 11 years? We don’t have that many contracts. Fiction likes our music and we like their way of doing business. When that’s no longer the case, we’ll end our cooperation.”

No Neil today:

The truth is hard to swallow. Even new wave pop idols have to pee. While Smith is away for a while, my eye falls on a copy of New Musical Express. On the front page, a couple of intriguing duets are named. Van Morrisson will sing along on the new record of Cliff Richard and Barney from New Order is in the studio with Pet Shop Boy Neil Tennant. The four gentlemen look proudly into the lens, but someone, Robert Smith probably, has blackened Neil Tennant beyond the point where you can recognise him.

HUMO: When was the last time you intended to dismantle The Cure?

Smith: “Last year, I really thought we had reached the end. Even during the recording of Disintegration I wasn’t thinking of going back on tour again.”

HUMO: Why?

Smith: “Playing in a group and touring is a very tiresome thing to do, both physically as well as mentally. And then I don’t even mention the hysteria that we were confronted with last time. Curemania gave a weird, unworldly dimension to the aspect of touring. It gave me a claustrophobic feeling; a feeling like someone had switched on a machine that couldn’t be stopped by anyone or anything. For the very first time, we felt like victims. It sounds dramatic, but the whole thing becomes so BIG that it overwhelms you. It’s like they set loose a beast on you. And there’s another thing. Not even in my wildest dreams did I see myself being 30 years old and still being on a stage. I thought I would that kind of guy who never has to shave and writes some film scores now and then.”

HUMO: Why do you still continue then?

Smith: “Now that we’re planning a tour again, I really find the idea of performing exciting again. Performance still is the main difference between rock and film music, literature or sculpting. In most art forms, you interpret the work of others or you create something that doesn’t have to be shown to an audience immediately. Only a rock group gives you the two dimensions. Making a record with The Cure and then not performing it live would be contradictory to what this band is all about (pauses). Well yeah, at the end of this tour, I will state the exact opposite again. If I then say that it was our last tour, I will be closer to the truth than now.”

HUMO: You sustained the mass hysteria of the South American rock audience. Are you a survivor now?

Smith: “I wouldn’t stress it that strongly, but there were moments where I thought I wouldn’t make it out alive. The organisation wasn’t good most of the time. I remember one time, I got out of the tour bus last and, further away, I saw that the security fences weren’t holding the fans anymore. A second later, I saw a herd of South Americans running wildly towards me. I had already progressed too far to run back to the bus. Everything happened in slow motion. I was nailed to the floor, saw them approach and knew they were after me. But at the same time, I could barely believe it. Wasn’t I just Robert, that kid that went to school in Crawley and when he looked in the mirror in the morning still had a face to punch? Eventually a security agent saved me from in between the crowd. Afterwards, I thought I had dreamt it all. It seemed too unlikely: you’re sitting in a bus, talking about trivial stuff and two minutes later you’re being run over by fans gone wild. The tour in South America probably was the next nail in the coffin of the operational Cure. When the hysteria reaches that level, it becomes a handicap. “

HUMO: How do you prevent something like that from happening? More security?

Smith: “You stay home (laughs). Not being famous is easy. And luckily only the South American people react that way. The Latin hysteria can be very violent and doesn’t consider the fragility of the human body at all. I had a feeling they really considered me to be some kind of superhuman. They thought I would lift off just before the crowd surrounded me – a painful mistake. We can’t complain. Most fans respect our private lives. From our music, they get the idea that we are very quiet and introvert people. They don’t want to demand us too much cause they know our music struggles in that same kind of feeling of doubt of acting upon something. Sorry, but now we really should be ending this.”

HUMO: One last question then: you played with The Cure your whole adult life. If you could start with a clean sheet tomorrow, how would the personal ad read?

Smith: (giggles) “Let me think (actually thinks), maybe like this: Failed singer searches a job as lazy guitarist. Or hysterical drug addict searches membership of group of people living in complete abstinence.”

Thanks so much - Jeroen (MFC) for TRANSLATING....